|

|

|

|

|

RECONSTRUCTING USER ACTIVITY THROUGH BROWSER FORENSICS BY EXAMINING TECHNIQUES AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Priya Kumari 1![]() , Dr. Kapil Shukla

2

, Dr. Kapil Shukla

2![]() , Dr. Krishna Modi 2

, Dr. Krishna Modi 2![]()

1 Student at School of Forensic Science, National

Forensic Sciences University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

2 Assistant

Professor at School of Forensic Science, National Forensic Sciences University,

Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

It is a study

based on the importance of web browsers as we use it in everyday life and

primary sources of online evidence for investigation. This perspective

extends beyond the technical, including the human and investment aspects that

create the constant evolution of browser forensics over recent years. By

examining research that utilizes a range of forensic tools and methodologies

and also the study identifies how investigators extract and analyze these

artifacts to reconstruct timelines, track user actions, and recover deleted

and hidden information. As with the time browsers continue to integrate

advanced privacy features with synchronization across devices and stronger

encryption forensic methods must evolve accordingly. This review highlights

how advancements in technology compel ongoing improvements in forensic

strategies and emphasizes the need for adaptive, ethical, and well-validated

approaches. By the advancements of browser usage, the potential for

cybercrime is also increasing and by that it is very crucial for

investigators to understand browser forensics to retrieve the essential

evidences. Researchers have to work

ethically and balancing rigorous forensic analysis with concerns about

preserving user’s privacy, and most of the research reviewed in this paper

discussed about this dilemma. This study analyses and examines browsers

artifacts e.g. cache, cookies, and history in normal, private, and portable

modes in different commonly used browsers by using different multiple tools

and methodologies.it also helps to recover meeting data, user details, and

encrypted content by memory and browser forensics in SaaS platforms. The

paper discussed how technological development compels forensic methods to

evolve continuously. |

|||

|

Received 28 October 2025 Accepted 15 November 2025 Published 03 December 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Kapil

Shukla, kapil.shukla@nfsu.ac.in DOI 10.29121/DigiSecForensics.v2.i2.2025.67 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Browser Forensics, Memory Forensics, Browsing Modes,

Artifact Recovery, Volatile Data, SaaS Platforms |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

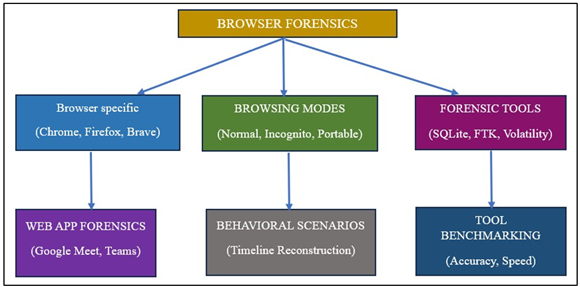

Browsers are more than internet-using tools they are portals for communication, purchasing, entertainment, and information gathering. Web forensics is a specialized branch of digital forensics i.e. based on identification, collection, and preservation of digital evidences that are automatically created by the user’s-based activities. In the realm of forensics, browsers present useful stores of evidence, with residues of user behavior in the form of caches, cookies, histories, form data, downloaded files, saved passwords search queries, of browsing, and session logs. Browser forensics is used in crimes like fraud, cyberstalking, and terrorism which needs useful information about criminal activity. Web browser is such a dynamic subject that needs attention in all directions i.e., technical and human and research. There is a huge amount of data to be analyzed during investigation beside keeping in mind about its privacy and this includes a range of taxonomies Figure 1, and we derive detailed information from these forensic methods used in browser forensics.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Taxonomy of Browser Forensic Research |

1.1. Challenges in web forensics

Web forensics deals with a bunch of challenges specially related to data volatility and distribution that are not in case of traditional system forensics. Web browsers simultaneously create, modify and delete temporary files during user’s sessions. Nowadays, many advance web applications operate on cloud storage and server-side architecture, that minimizes the digital traces on local machines. Also, private browsing modes, encrypted connections (HTTPS), and content delivery networks (CDN) makes it even challenging to extract important evidences for investigator.

1.2. Browser forensics techniques

Browser forensics involves systematically collecting and detailed analyzing digital traces that are left behind by web browsers to reconstruct user activity. Several techniques are commonly used to extract and interpret these artifacts.

Browser history analysis is a fundamental method that retrieves lists of visited websites, timestamps, and access frequency. This helps investigators to derive user intent, navigation patterns, and behavior over time. In addition to this is cache analysis, which analyses locally stored files such as HTML pages, scripts, images, and stylesheets that browsers save to speed up loading times. These cached components can reveal detailed insights about the user’s browsing sessions, even when history entries are erased. Analyses of cookies focuses on small text files that store login tokens, session identifiers, and site preferences. Cookies play a crucial role in uncovering user accounts accessed and can sometimes shows authentication tokens valuable for tracking user activity. Analysis of Bookmark and Downloads also provide details about user intent, interests, and file acquisition behavior, that can reveal potential motivations behind browsing activities. Another important technique is analysis of password, which examines stored credentials saved in browser databases. This helps investigators understand which online platforms the user was using and whether compromised passwords might have been reused somewhere else. Memory analysis is one of the most important techniques that focuses on examining RAM of system to extract transient data from active browsing sessions. The volatile memory contains unencrypted and temporary artifacts like session cookies, chat logs, encryption keys, and user identifiers it plays an important role in cases involving private browsing or web based applications. Cloud-based and extension analysis investigates evidence within online storage services and browser extensions. These components can reveal user behavior related to file uploads, sharing, downloads, or identity masking (e.g., via VPN or privacy extensions). Altogether, these techniques form the backbone of browser forensics, allowing investigators to reconstruct digital activities systematically across both local and cloud environments.

1.3. Motivation of this review article

Research in the field of web browser forensics shows some observable gaps. Web forensics act as a very crucial evidence artifact during investigation that can be acceptable by court of law. Cross browser synchronization artifacts and privacy related browsers such as Brave and Tor remain less explored leaving uncertainties about cloud based and memory level evidence recovery. Some studies examine how continuous browser updates affect artifact skeleton, and systematic benchmarking of forensic tools is limited. Research on private browsing, their extensions, and plugins is not complete, while application-based forensics beyond platforms like Google Meet and Teams is rare. Moreover, most analyses still rely on manual extraction methods, shows the need for automated, integrated frameworks for real-world investigations.

2. Structured Literature Review

Mostly studies are based on common browser like Chrome, Firefox, edge. In these researchers extensively studied cache files, cookie storage, and encrypted storage. Use of technical decoding of SQLite stores, JSON stores, and proprietary caching systems are done during investigations.

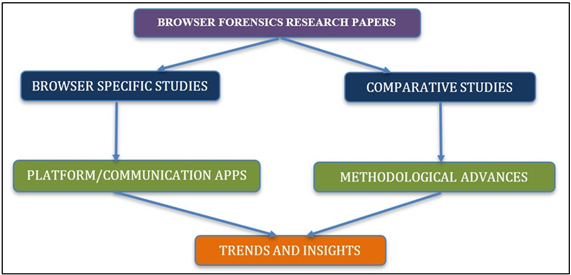

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Illustrates Flow Chart of the Conceptual Structure of Browser Forensic Research. |

Different browser stores forensic evidence in different methods that can be compared and studied. Like the incognito mode minimize the recoverability of digital traces Figure 2.While in normal mode it is easier to track digital traces. These technical differences give a vast information and act as an investigation aid. This is why browser forensic is dynamic research. That is why researchers work in an anonymous system and then incorporate new findings and research in the discussions Chand et al. (2025), Leith (2021). Research into communication platforms such as Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, and Zoom acknowledges that forensic footprints continue long after browsers themselves are gone. Session tokens, temporary files, and logs often spill over into browser storage with the recording of evidence trails in spite of platforms making claims to security Iqbal et al. (2022).

The systems, their environment and the forensic tools are continuously evolving. These are the most important area for browser artifact analysis. Investigators typically use software such as FTK Imager, Autopsy, OSForensics, Browser History Examiner, and Volatility. These tells about user history, cache, cookie, and various browser residues extraction and rebuilding, with clear information of online activities. Some researchers conducted remarkable researches that gives detailed studies on analysis of browser data with the above stated tools on various platforms researchers Alotibi et al. (2024). Artifact recovery and memory forensics is another area that is proving crucial with analysts utilizing Volatility, Bulk Extractor, Photorec, FTK Imager, and OSForensics for further, Realtime data recoveries from volatile memory. It reveals fleeting data shadows that are ignored by classic disk forensic techniques i.e., the most significant in terms of retrieving live session data, as demonstrated by Alotibi et al. (2024), Iqbal et al. (2022). Comparative analysis of forensic software also is crucial. This study compares suites such as Browser History Examiner and RS Browser with different browsers in order to reveal their strengths and weaknesses, for the purpose of developing better forensic tools. Some research provides real-world observations about tool efficiency Chand et al. (2025).There are professionals that specialize in browser-related forensic techniques, examining Chrome, Firefox, and Brave with ChromeCacheView or NirSoft like programs or specialized scripts that account for the nuances of each platform Akintola (2024) To seize live system and kernel-space analysis, open-source tools e.g. Kali Linux as well as Parrot OS can be used. They are extensively used in dynamic extraction of evidence Qureshi et al. (2022).

Cloud forensics is one of the most challenging and complex field as it includes virtual and vastly distributed digital data. Here, tools like Magnet AXIOM Cloud, Cellebrite UFED Cloud Analyzer, Mandiant Cloud Lens, to the Volatility Framework are used with cloud-native tools such as Azure Security Centre and AWS CloudTrail to facilitate multi-layered acquisition of distributed data from cloud environment Adesina et al. (2022). Some cases involve data encryption and privacy of data user which makes it challenging. Examiners use a powerful combination of FTK, EnCase, Wireshark, Autopsy, and network analysis software such as SANS Investigative Forensics Toolkit (SIFT), NetworkMiner, Bro/Zeek, and Suricata in order to decipher obfuscations and follow privacy leaks the foundation of findings by several researchers Adesina et al. (2022).Forensics in online communications such as GoToMeeting and Discord use a combination of disk analysis (Autopsy), memory analysis (Volatility), and network traffic capture by Wireshark, to which we add purpose-made specialist forensics software for such applications. These techniques give us greater ability to recover conversation logs and user contacts, as highlighted in recent literature by Tiwari and Kashyap (2025).System architecture-focused forensics aim for system architecture, particularly Windows 10 and Mac OS X, utilizing native forensics suites combined with tools such as Autopsy for maximal extraction of contextualized evidence based on OS behaviour, as argued by researchers Rathod (2017), Kauser et al. (2022).

Finally, reviews comprehensively examine commercial and open-source forensic tools, from FTK to Autopsy, EnCase, The Sleuth Kit, SIFT, X-Ways Forensics, Wireshark, NetworkMiner, and the Digital Forensics Framework (DFF), including essential information and forensics best practice guidance Rasool and Jalil (2020).

As the Table 1. shows, tools like Wireshark, NetworkMiner (network sniffers), Bro/Zeek, Suricata and memory capture tools like Volatility and FTK, with firewall gives logs examination and timeline that enquires about user’s behavior and personal. This facilitates user behavior nuances as well as violation of privacy tracing Liou et al. (2016), Zhao and Liu (2015), Ruiz et al. (2015), Satvat et al. (2014)

Table 1

|

Table

1 Overview of Research Groups in Web Browser

Forensics that Includes Methods, Tools, and Key Studies |

|||

|

Group |

Methods Used |

Tools Used |

Papers

Included (References) |

|

1 |

Comprehensive Browser Artefact Analysis |

FTK

Imager, Autopsy, Browser History Examiner,

OSForensics, Volatility |

Flowers et al. (2016) |

|

2 |

Memory Forensics

and Artefact Extraction |

Volatility, Photorec,

Bulk Extractor, FTK Imager, OSForensics |

Tiwari, and Kashyap (2025), Iqbal et al. (2022), Rathod (2017) |

|

3 |

Comparative Forensic Tool Evaluation |

Browser History Examiner, Browser History View,

RS Browser, OS Forensic |

Chand et al. (2025), Akintola (2024), Nalawade et al. (2016). |

|

4 |

Browser-Specific Forensics on Chrome, Firefox, Brave |

ChromeCacheView, NirSoft, Custom Scripts |

Fernández-Fuentes et al. (2022), Mahaju and Atkison (2017), Ntonja and Ashawa

(2018). |

|

5 |

Forensic Acquisition with Kali Linux and Parrot

OS |

Kali Linux Forensic Tools, Parrot OS Forensics

Tools |

Qureshi et al. (2022). |

|

6 |

Cloud Storage and Hybrid Data Hiding Forensics |

Magnet AXIOM Cloud, Cellebrite UFED Cloud

Analyzer, Mandiant CloudLens, Volatility Framework,

AccessData Cloud Extractor, Oxygen Forensic Cloud

Extractor, Autopsy, BlackBag BlackLight, X-Ways Forensics, Azure Security Center, AWS CloudTrail, Paraben Cloud Analyzer, Belkasoft Cloud Extractor, Elcomsoft

Cloud Explorer, MSAB Cloud Analyzer |

Adesina et al. (2022), Amran et al. (2020). |

|

7 |

Private Browsing and Privacy Breach Analysis |

FTK, EnCase, Wireshark, Autopsy, SANS

Investigative Forensics Toolkit (SIFT), Wireshark, NetworkMiner,

Bro/Zeek, Suricata, Firewall logs analysers |

Satvat et al. (2014), Ruiz et al. (2015), Zhao and Liu (2015), Flowers et al. (2016), Tsalis et al. (2017), Saidi et al. (2018), Amran et al. (2020), Mahlous, and Mahlous

(2020), Kathiravan et al. (2020), Fayyad-Kazan et al. (2021) |

|

8 |

Communication Apps Forensics (Discord, GoToMeeting) |

Volatility, Autopsy, Wireshark, Discord Forensic

Tools |

Motyliński et al. (2020), Tiwari and Kashyap (2025). |

|

9 |

OS

Specific Forensics (Windows 10,

Mac OS X) |

Windows Forensic Toolkit, Mac Forensic Tools,

Autopsy |

Kauser et al. (2022), Rathod (2017) |

|

10 |

Forensic Tools and Methodology Reviews |

FTK, Autopsy, EnCase, The Sleuth Kit, SANS

Investigative Forensics Toolkit (SIFT), X-Ways Forensics, Wireshark, NetworkMiner, Digital Forensics Framework (DFF) |

Rasool and Jalil (2020), Mahaju and Atkison (2017), Qureshi et al. (2022), Alotibi et al. (2024), Akintola (2024), Chand et al. (2025), Mugisha (2018). |

|

11 |

Behavioral and

Privacy Studies with Network Analysis |

Network sniffers (Wireshark, NetworkMiner,

Bro/Zeek, Suricata), memory capturing tools (e.g. Volatility, FTK), firewall

logs analyser, forensic timeline examination tools |

Khalid et al. (2022), Kauser et al. (2022) |

Browser specific forensic studies make us understand about how digital impressions are left behind by most used browsers. One important study focused on Chrome examining its artifact storage over versions released between the years of 2022 and 2024. By simulating real world browsing activities on Windows 10 and Ubuntu systems and leveraging tools like SQLite Browser, Autopsy and FTK Imager. Some researchers found that in spite of Chrome’s evolving privacy properties, important artefacts on in several key databases Mugisha (2018). Also, what makes it interesting was the discovery that changes in Chrome’s history database schema after version 114 introduced new challenges in parsing data automatically. This understanding shows that how critical it is for forensic tools to be regularly updated to keep pace with browser advancements Alotibi et al. (2024). At the same time, the privacy claimed by Firefox's private browsing was also tested. By experimentation with private browsing sessions and Volatility and Autopsy-based memory analysis, researchers established that few data remain in long-term persistent storage, but volatile memory as well as swap files persist with temporary artifacts session tokens and open tab data that can be retrieved shortly after closing a session. As such, the private browsing, as effective, is far from being proof against being discovered through forensics, and live capture of memory is still indispensable in investigations Mahaju and Atkison (2017).

The Brave Browser, created with privacy as a primary concern, was also put through the test of forensic footprints. Researchers mimicked actions such as streaming videos and operating cryptocurrency wallet management, inspecting Brave's SQLite database files, cache directories, and memory dumps with Autopsy, FTK Imager, and in-house Python scripts. Their results indicated that, although Brave restricts long-term storage of browsing data, some temporary files and wallet information remained recoverable. It was the first time that the entire Brave forensic landscape was investigated, finding that privacy-minded web browsers still contain traces useful in forensics Mahlous, and Mahlous (2020). If we consider different modes, a relative study of Chrome's incognito, normal, and portable modes found a distinctive gradient in recoverable artifacts. Normal browsing was most recoverable i.e. Approximately 90%, while portable mode was slightly recoverable i.e. Approximately 60%. Incognito mode was minimally recoverable i.e. approximately 40%, with much of it recoverable in only volatile memories and swap files. Similar results were also found in Firefox and Microsoft Edge, with Edge surprisingly giving more recoverable artifacts in privacy mode than Firefox, thereby questioning pre research assumptions about the privacies of modes of browsing. This concludes that while privacy and portable modes decrease traces, they barely guarantee full anonymity Ntonja and Ashawa (2018), Rathod (2017).

The comparison of the forensic tools also provides more detail on their weaknesses and strengths. SQLite Browser was applauded for being amazing with structured data including history and cookies. Autopsy was good with timeline reconstruction, FTK Imager was good for extracting multimedia cache. Volatility was needed for volatile memory analysis although with some limitations, and EnCase was all encompassing but used more system resources. The comparison given above shows the importance of utilizing a range of tools for all encompassing coverage in forensic analysis Alotibi et al. (2024).

The web app forensics more emphasising on enterprise video conferencing was another remarkable area as well. Researchers who analyzed Google Meet sessions in Chrome and Mozilla Firefox unveiled a slew of artifacts from meeting IDs and participant listings to cached thumbnails and chat logs stored in browser caches and local repositories. Team vs GoToMeeting comparisons also give insight that the Teams had retained vastly more highly detailed, highly structured traces, with GoToMeeting artifacts largely being cached chunks of video or audio. The results demonstrate that communication applications are a treasure trove of rich forensic evidence because we need to utilize specialized procedures as the applications differ to such an extent Iqbal et al. (2022), Khalid et al. (2022). Based on the browser forensic evidences, investigators can study the behaviour and can reconstruct the timelines and can established the motives behind its actions. It gives comprehensive detail about user’s financial activities, social connections by the help of pirating files in combination with memory screenshots and system logs, and with browser artifacts produced by the user itself unknowingly. These techniques bring the effectiveness of browser forensics from data finding to an understanding of intent and context, of value in corporate as well as legal investigations Chand et al. (2025).

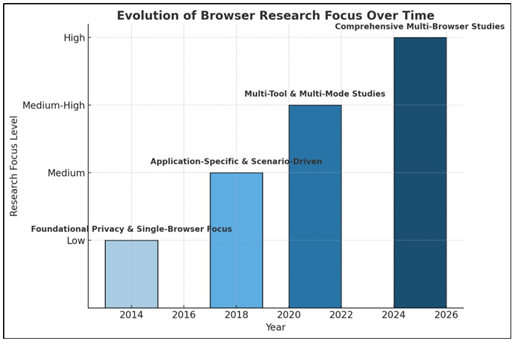

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Illustrates Trend Followed in Research Methodology Sophistication Over the Years from 2014 to 2025 (Conceptual Timeline) |

Earlier works (pre-2018) generally consisted of controlled surfing in one mode or browser, with subsequent disk analysis Tiwari and Kashyap (2025). The intermediate phase witnessed the popularity of scenario-based testing Figure 3 for particular applications such as cloud services and Discord Motyliński et al. (2020), Adesina et al. (2022). Some studies utilize factorial designs that test in parallel more than one browser, browsing modes (normal, portable, private), and forensic instruments. This facilitates strong comparative inferences about the persistence of artifacts as well as the effectiveness of tools that could not by and large be made in prior, more limited works. Cumulative basic browser mechanics research accounts for a full 65%—either through generic comparison and analysis of tools (35%) or specifically through investigation of the effectiveness of the private browsing modes (30%). Forensic analysis of particular web applications accounts for the remaining 35%, of which much is in turn committed to conferencing applications in recognition of their practical real-world significance

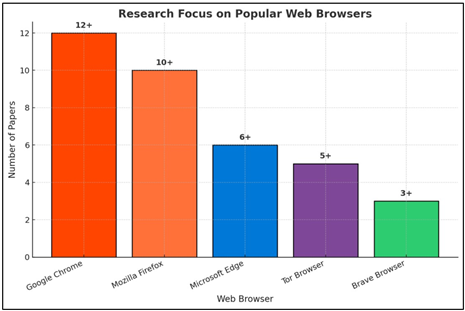

The coverage of personal browsers in literature is inconsistent. The following table details literature coverage of specific browsers, their market penetration and/or unique forensic value.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Analysis of Browsers Covered in the Reviewed Literature |

Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome are most actively studied Figure 4 consistent with their enormous user bases. The significant amount of study of privacy-focused web browsers like Tor and Brave is an indicator of the research community's enthusiasm to extend the limits of privacy and anonymity Mahlous, and Mahlous (2020), Sanghvi et al. (2024), Sanghvi et al. (2023)

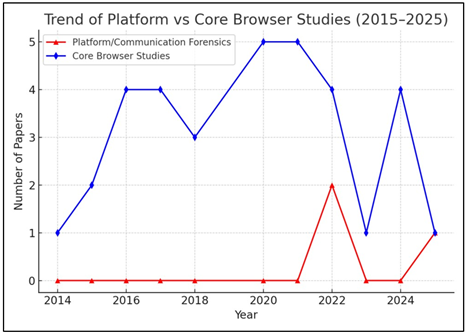

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Publication Trend of Platform/Communication Forensics vs Core Browser Studies (2015–2025) |

The transition of research interest from core browser research to platform or communication forensics from 2015 to 2025 Figure 5. During the earlier years, the majority of studies were focused on core browser features, with the maximum being attained around 2020 to 2021 and then declining at a steady pace. Conversely, platform and communication forensics research remained negligible until 2021, but from then on, it began attracting interest with steadily increasing growth. This pattern indicates that researchers are moving from more classic, browser-oriented research to upcoming topics associated with platforms, communications tools, and traditional web environments with new opportunities for new studies in the future.

3. Methodology

Research studies are extensively based on its relevance, forensic information, and methodology used. Studies are grouped into: browser focused studies, comparison studies, application based forensic studies and methodology based.

3.1. Methodologies used according to the browsers, privacy modes, and communication platforms

The methods to extract traces in web browser forensics keep changing and evolving over time. Users use sophisticated browsers act as a huge challenge for investigators that needs specific methods to extract useful information that can link the investigation.

One of the important research projects is that questions online privacy. In some research browsers are used in private modes and then forensically the hard drive data was captured and registry of the computer was analysed to see traces of the user. This basic approach of first “use it and then see what remains" remain as one of the preliminary studies on this topic. Building on this, some researchers expanded the scope by testing browsers not just in private mode, but also when run from a USB stick, using advanced data carving techniques to find hidden artifacts. The studies show different scenarios extended to cybersecurity simulated peer to peer (P2P) network attacks through a browser and combining it with network examination with conventional artifact hunting to trace anonymous activity Kauser et al. (2022). Some researchers designed tests based on real world tasks like streaming videos or checking email across different browsers to see exactly how the actions are recorded. The most amazing comparison to date came from some researchers who created a massive test Chand et al. (2025). They put five individual browsers through normal, private, and portable modes, using a whole set of tools to see which combinations left the minimum traces. At the same time other researchers have zoomed in on specific apps. for instance, focused entirely on Discord, simulating chats and file shares and then combing through the app's local cache and network traffic for evidence Motyliński et al. (2020).

This pattern of specialisation continued as our online lives became more platform focused. Some stood out by using solely free, open-source forensic software from Kali and Parrot OS to find out what evidence they could reliably find. As video conferencing became central, researchers applied the methods used for other sites to GoToMeeting Tiwari and Kashyap (2025); Qureshi et al. (2022) with controlled sessions then trawling RAM and disk for information related to online meetings. Some researchers also found about the failures of complete privacy features, e.g. how information can leak accidentally by just means of a browser extension, even from a private browsing tab. Also, some studies are significant in activities within browses on different systems. Researcher compared the privacy-minded Tor Browser on Windows desktops to that on Android mobile phones, with tools that were applicable to each one, to determine whether the anonymity continued to be .Some then offered the detail of particular browsers, including forensic tools specific to Firefox as well as investigating the depth of a particular build of Chrome .Researchers then went on to develop specialized methods to investigate private browsing itself on Linux as well as to compare the results to that on Windows .

Researchers have also examined a large data from cloud storage and uses services like iDrive through a browser and then forensically recovering file metadata and login traces that gives information about user’s psychology Adesina et al. (2022). Some researchers studied both simultaneously technology with human element and found overconfidence leads people to leak information even in private mode. And also studied about Mac systems, and applied specialised techniques to find browser artifacts within the macOS system Rathod (2017).

The evolution of methodologies in extraction shows clearly that sophistication of forensic testing increased over time. Initially it was important to develop baseline evidence maps for Windows 10 browsers Also, some studied particular browser in detail including case studies of particular browsers such as Brave and also compare their standard and private modes for differences. Some researchers used simulations of Microsoft Teams meetings under a corporate-style and found evidences traces in browser caches and temp folders (Khalid et al., 2022). Some researchers inspect internal databases after regular and incognito sessions of browsers like chrome. These standard methods were used in some past researchers, which act as a base work for acquiring browser evidence. On the flip side, some researchers operated from an anti-forensic angle, creating and testing hiding methods for data to ensure browser activity is more difficult to track.

Underlying all of these activities is the critical assessment of the forensic tools themselves. Some research systematically reviewed then rigorously benchmarked well known forensic tools and compare their accuracy, comprehensiveness, and speed in order to assist investigators in selecting the appropriate one for the task. This task-oriented testing can be witnessed in research who stresstested tools against who did a deep probe of Firefox's particular storage mechanisms. Ultimately, was a pioneer of the area of browser-based conferencing forensics by grabbing the memory and disk after the completion of Google Meet sessions in order to retrieve meeting IDs and chat snatches.

4. Research Gaps in Current Web Browser Forensics Literature

Current browser forensics research reveals some key gaps. Most researches focus on desktop browsers and overlooking mobile platforms like Android and iOS even though their dominance and individual challenges such as sandboxing and OS fragmentation. Cross device sync artifacts are less explored especially in terms of forensic extraction and cloud related chain of custody considerations. And, there are new versions of browser coming in every few months that need updates and need new studies to continuously performed and new loopholes can be discovered. Privacy centric browsers like Brave and Tor receive limited analysis, even though their features like ephemeral storage, onion routing and ad blocking demand deeper forensic studies. Research also lacks longitudinal studies on how recent browser updates impact structure of artifacts. There are very few studies in which forensic tools are benchmarked systematically and also with little comparison across commercial and open-source options. Artifacts based on private browsing are irregularly analyzed, with no cross-browser matrix to authenticate extensions that claims privacy and plugins which store sensitive data are mostly ignored Application-level forensics is limited to a few platforms, leaving out famous services e.g., Google Drive, WhatsApp Web & Slack. Finally, most artifact extraction remains manual, highlighting the need for automated, integrated forensic frameworks.

5. Conclusion

Web browser forensics remains fundamental to modern day digital forensics that requires collaboration between developers, forensic experts and attorneys. Features like encryption, privacy controls and growing data act as huge challenges during investigations. This field must act as middle ground between technical advancement and privacy related concerns. Studies have found schema changes for privacy limitation and memory dependence for Firefox and Chrome. Mobile and incognito modes reduce but do not entirely erase traces of browser activity. Tool examination both highlighted weaknesses and strengths of forensic software as well as extended their scope to cover web applications used in enterprise situations. Behavioral studies proved useful for rebuilding user timelines and intent Overall, the field is rapidly evolving, and forensic tools and processes must adapt in response.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None .

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Adesina, A., Adebiyi, A. A., and Ayo, C. (2022). Detection and Extraction of Digital Footprints from the iDrive Cloud Storage Using Web Browser Forensics Analysis. International Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 26(1), 550–559. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v26.i1.pp550-559

Akintola, G. B. (2024). Performance Evaluation of Four Different Forensic Tools for Web Browser Analysis. International Journal of Scientific Research in Multidisciplinary Studies, 10(10), 68–82.

Alotibi, A. M., Altaleedi, S. Y., Zia, T., and Qazi, E. U. H. (2024). Examining the Behavior of Web Browsers Using Popular Forensic Tools. International Journal of Digital Crime and Forensics, 16(4). https://doi.org/10.4018/IJDCF.349218

Amran, M. F. M., Kathiravan, Y., Razali, N. A. M., Ahmad, R. M. T. R. L., Adnan, Z., Rauf, M. F. A., and Shukran, M. A. M. (2020). Secure User Browser Activity Using Hybrid Data Hiding Techniques. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, 9(1), 595–598. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.A2015.059120

Chand, R. R., Sharma, N. A., and Kabir, M. A. (2025). Advancing Web Browser Forensics: Critical Evaluation of Emerging Tools and Techniques. SN Computer Science, 6(4), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-025-03921-6

David Mugisha. (2018). Web Browser Forensics: Evidence Collection and Analysis for Most Popular Web Browsers Usage in Windows 10. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, 54(Cyber Investigation), 12. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.25857.51049

Fayyad-Kazan, H., Kassem-Moussa, S., Hejase, H. J., and Hejase, A. J. (2021). Forensic Analysis of Private Browsing Mechanisms: Tracing Internet Activities. Journal of Forensic Science and Research. https://doi.org/10.29328/journal.jfsr.1001022

Fernández-Fuentes, X., Pena, T. F., and Cabaleiro, J. C. (2022). Digital Forensic Analysis Methodology for Private Browsing: Firefox and Chrome on Linux as a Case Study. Computers and Security, 115, Article 102626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2022.102626

Flowers, C., Mansour, A., and Al-Khateeb, H. M. (2016). Web Browser Artefacts in Private and Portable Modes: A Forensic Investigation. International Journal of Electronic Security and Digital Forensics, 8(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESDF.2016.075583

Iqbal, F., Khalid, Z., Marrington, A., Shah, B., and Hung, P. C. K. (2022). Forensic Investigation of Google Meet for Memory and Browser Artifacts. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 41, Article 301448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsidi.2022.301448

Iqbal, F., MacDermott, A., Motyliński, M., and Hussain, M. (2020). Digital Forensic Acquisition and Analysis of Discord Applications. In 2020 International Conference on Communications, Computing, Cybersecurity, and Informatics (CCCI). https://doi.org/10.1109/CCCI49893.2020.9256668

Kathiravan, Y., Amran, M. F. M., Razali, N. A. M., Shukran, M. A. M., Wahab, N. A., Khairuddin, M. A., Ismail, M. N., Adnan, Z., and Rauf, M. F. A. (2020). A Study on Private Browsing in Windows Environment. Journal of Defence Science Engineering and Technology, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.58247/jdset-2020-0301-03

Kauser, S., Malik, T. S., Hasan, M. H., Akhir, E. A. P., and Kazmi, S. M. H. (2022). Windows 10’s Browser Forensic Analysis for Tracing P2P Networks’ Anonymous Attacks. Computers, Materials and Continua, 72(2). https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2022.022475

Khalid, Z., Iqbal, F., Al-Hussaeni, K., MacDermott, A., and Hussain, M. (2022). Forensic Analysis of Microsoft Teams Investigating Memory, Disk, and Network. In Digital forensics and cybersecurity (xx–xx). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-03106371-8_37

Leith, D. J. (2021). Web Browser Privacy: What Do Browsers Say When They Phone Home? IEEE Access, 9, 41615–41627. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3065243

Liou, J.-C., Logapriyan, M., Lai, T. W., Pareja, D., and Sewell, S. (2016). A Study of the Internet Privacy in Private Browsing Mode. In Proceedings of the 3rd Multidisciplinary International Social Networks Conference (xx–xx). https://doi.org/10.1145/2955129.2955153

Mahaju, S., and Atkison, T. (2017). Evaluation of Firefox Browser Forensics Tools. In Proceedings of the Southeast Conference (xx–xx). https://doi.org/10.1145/3077286.3077310

Mahlous, A. R., and Mahlous, H. (2020). Private Browsing Forensic Analysis: A Case study of Privacy Preservation in the Brave Browser. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering and Systems, 13(2), 306–315. https://doi.org/10.22266/ijies2020.1231.26

Motyliński, M., MacDermott, A. M., Iqbal, F., Hussain, M., and Aleem, S. (2020). Digital Forensic Acquisition and Analysis of Discord Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Communications and Cybersecurity (Vol. 10, 1–8). https://doi.org/10.1109/CCCI49893.2020.9256668

Nalawade, A., Bharne, S., and Mane, V. (2016). Forensic Analysis and Evidence Collection for Web Browser Activity. In 2016 International Conference on Automatic Control and Dynamic Optimization Techniques (ICACDOT) (xx–xx). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACDOT.2016.7877639

Ntonja, M., and Ashawa, M. A. (2018). Investigating Google Chrome 6603359 Artefact: Internet Forensics Approach. Journal of Computer Science and IT.

Qureshi, S., He, J., Qureshi, S.

S., Zhu, N., Rajputt, F. A., Ullah,

F., Nazir, A., and Wajahat, A. (2022). Browser Forensics Extracting

Evidence from Browser Using

Kali Linux and Parrot OS Forensics Tools.

International Journal of Scientific Research in

Computer Science and Engineering, 10(5).

Rasool, A., and Jalil, Z. (2020). A Review of Web Browser Forensic Analysis Tools and Techniques. International Journal of

Computer Applications, 182(20), 1–15.

Rathod, D. M. (2017). MAC OSX Forensics. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Engineering and Technology.

Rathod, D. M. (2017). Web Browser Forensic: Google Chrome. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science, 8(7). https://doi.org/10.26483/ijarcs.v8i7.4433

Ruiz, R., Winter, R., Winter, K., Park, F., and Amatte, F. (2015). Overconfidence and Personal Behaviours Regarding Privacy that Allows the Leakage of Information in Private Browsing Mode. International Journal of Cyber-Security and Digital Forensics, 4(3), 404–416.

Saidi, R. M., Udin, F. F. S., Zolkeplay, A. F., Arshad, M. A., and Sappar, F. (2018). Analysis of private browsing activities. In A. R. Abdullah et al. (Eds.), Regional Conference on Science, Technology and Social Sciences (RCSTSS 2016) (217–228). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-00745_20

Sanghvi, H., Rathod, D. M., Altaleedi, S. Y., AlThani, A. S., Alkhawaldeh, M. A. A., Almorjan, A., Shah, R., and Zia, T. (2023). Google Chrome Forensics. International Journal of Electronic Security and Digital Forensics, 15(6), 591–619. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESDF.2023.133968

Sanghvi, H., Rathod, D., Shukla, P., Shah, R., and Zala, Y. (2024). Web browser Forensics: Mozilla Firefox. International Journal of Electronic Security and Digital Forensics, 16(4). https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESDF.2024.10055704

Satvat, K., Forshaw, M., Hao, F., and Toreini, E. (2014). On the Privacy of Private Browsing—A Forensic Approach. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2014.02.002

Tiwari, S. K. P., and Kashyap, N. (2025). Forensics Analysis of Browser-Based Gotomeeting Clients: Uncovering Memory and Browser Artefacts. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management, 10(20s). https://doi.org/10.52783/jisem.v10i20s.3172

Tsalis, N., Mylonas, A., Nisioti, A., Gritzalis, D., and Katos, V. (2017). Exploring the Protection of Private Browsing in Desktop Browsers. Journal of Privacy and Confidentiality, 9(2), 45–66.

Zhao, B., and Liu, P. (2015). Private Browsing Mode: Not Really that Private? Dealing with Privacy Breach Caused by Browser Extensions. In 2015 45th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN) (xx–xx). https://doi.org/10.1109/DSN.2015.18

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© DigiSecForensics 2025. All Rights Reserved.