|

|

|

|

|

AI-Based Deradicalization: Opportunities, Risks, and Case Studies

1 University

of Indonesia, Indonesia

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Radicalization

is a multifaceted process characterized by the embrace of extreme ideologies

and actions that contravene societal norms, potentially culminating in

violent extremism. Deradicalization, or more broadly, countering violent

extremism (CVE), encompasses the processes, initiatives, and interventions

aimed at reversing or counteracting radicalization, facilitating individuals'

disengagement from extremist ideology or behaviors. Recent studies underscore

the increasing significance of artificial intelligence (AI) in combating

online extremism and facilitating deradicalization initiatives. AI tools are

being developed to identify extremist content, forecast at-risk individuals,

and study the communication patterns and propaganda tactics of extreme groups,

especially on social media platforms. These platforms can distribute

counter-narratives and positive representations to contest extreme ideas;

nevertheless, their efficacy relies on ethical and responsible

implementation, along with interdisciplinary collaboration. Although

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a potential instrument in various

fields including extensive data, pattern recognition, personalization,

automation, and decision support, there is a paucity of research about the

application of AI in the deradicalization of terrorist criminals within

correctional facilities. This study aims to examine the prospects, risks, and

trajectories of AI-based deradicalization. This study seeks to comprehend the

role of AI in deradicalization efforts. This study identified ways for

implementing AI-based deradicalization through a literature analysis and

interviews with cyber and deradicalization specialists, as well as past

terrorist offenders, which are included in the RARE Model (Relation-Assistance-Reintegration-Evaluation).

This research may assist practitioners or governments in executing AI-driven

deradicalization initiatives. |

|||

|

Received 28 October 2025 Accepted 29 November 2025 Published 15 December 2025 Corresponding Author Zora A. Sukabdi, zora.arfina@ui.ac.id DOI 10.29121/DigiSecForensics.v2.i2.2025.63 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Counterterrorism, Artificial Intelligence,

Terrorism, Deradicalization, Extremism |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Radicalization is a complex process involving the adoption of extreme beliefs and behaviors that violate social norms, potentially leading to violent extremism Kruglanski et al. (2014). The process represents a gradual escalation from nonviolent to increasingly violent repertoires of action, developing through complex interactions over time Porta (2018). Key factors influencing radicalization include the quest for personal significance as a primary motivational force, ideological components that justify violence, and social networking processes that reinforce extremist beliefs Kruglanski et al. (2014). Political opportunities, organizational resources, and framing processes also affect strategic choices toward radical action Porta (2018). Multiple types exist, including political, religious, and social radicalization, influenced by social, economic, psychological, and online factors.

Deradicalization (or more broadly, countering violent extremism, CVE) refers to the processes, programs, and interventions that seek to reverse or counteract radicalization, helping individuals disengage from extremist ideologies or behaviour Sukabdi (2025). Deradicalization lacks a universally accepted definition but is generally understood as the process of changing attitudes and behaviors of former terrorists to reject violence as an ideological, religious, or political goal Aslam (2020). The concept involves both cognitive departure from radical ideology and behavioral shift away from radical activities and group membership Leap and Young (2021). Sumarwoto et al. (2020) define deradicalization as reinterpretation of "deviated" beliefs through efforts to reassure radical groups not to use violence while creating environments sterile from radical movements. Deradicalization programs typically focus on re-education to correct political and religious misconceptions, and rehabilitation involving continuous monitoring after release Aslam (2020). These programs utilize holistic approaches incorporating personality development, self-reflection, social skills, spirituality, and psychological tools Aslam (2020). From an Islamic perspective, deradicalization encompasses recognition of mistakes, repentance, apologies to affected parties, and commitment to improvement Sholehuddin et al. (2024).

Recent research highlights the growing role of artificial intelligence (AI) in countering online extremism and supporting deradicalization efforts. AI technologies are being developed to detect extremist content, predict at-risk users, and analyze the communication flows and propaganda strategies of radical groups, particularly on social media platforms Fernandez and Alani (2021). These systems can also disseminate counter-narratives and positive representations to challenge extremist ideologies, though their effectiveness depends on ethical and responsible deployment, as well as collaboration across disciplines Irfan et al. (2023). Additionally, AI can facilitate moderate religious communication by identifying sensitive issues, tailoring contextually relevant material, and fostering constructive dialogue, thereby promoting tolerance and reducing extremism Wahyuni et al. (2025). Despite these advancements, challenges remain, including data verification, evolving extremist behaviors, and the integration of social theory into technological solutions Fernandez and Alani (2021).

While Artificial Intelligence (AI) has in recent years become a promising tool in many domains involving large-scale data, pattern recognition, personalization, automation, and decision support; there is a limited study on the use of AI in deradicalization. This study therefore is held to explore and investigate the opportunities, risks, and directions of AI-based deradicalization. This study aims to understand how AI contribute to deradicalization, which is to answer this question: can AI meaningfully contribute to deradicalization? If yes, in what ways, and with what constraints? This study may help practitioners or governments in implementing AI-based deradicalization.

2. Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The concept of artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved significantly since the mid-20th century, with various definitions emerging across different domains. AI is fundamentally defined as the ability of machines and computer systems to perform tasks typically requiring human intelligence, including learning, decision-making, and data analysis Nedilko (2024). Existing definitions can be categorized into two groups: those characterizing AI as a field of scientific knowledge and those describing features of specific devices or systems Nedilko (2024).

The definitional landscape includes both informal approaches, such as programs "cleverer than humans," and formal definitions that avoid human-centric references Dobrev (2013). As AI systems become increasingly capable, the field of Advanced AI Governance has emerged, requiring clearer conceptual frameworks Maas (2023). For HCI researchers, understanding AI's complexities (including its definitions, concepts, and terminology) is crucial for developing safe and trusted applications Karam and Luck (2023).

3. Strategies of Deradicalization

Deradicalization strategies encompass comprehensive approaches aimed at rehabilitating former terrorists and countering violent extremism through systematic methods. Deradicalization programs globally utilize various methods including holistic personality development, self-reflection, social skills training, crime behavior modification, spirituality, and psychological support Aslam (2019). Countries like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Malaysia have implemented programs focusing on re-education to correct political and religious misconceptions, combined with rehabilitation strategies for post-release monitoring Aslam (2019).

Koehler (2016) emphasizes that effective deradicalization requires context-specific approaches, comprehensive understanding of radicalization mechanisms, and locally-adapted models based on proven quality standards rather than one-size-fits-all solutions. The Lingkar Perdamaian Foundation in Indonesia employs a humanistic approach based on Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs, implementing three key strategies: ideological development, family assistance for ex-terrorist convicts, and economic recovery Noor (2021). This approach addresses underlying motivations for terrorist involvement and promotes inclusive understanding while fostering love of country and respect for differences.

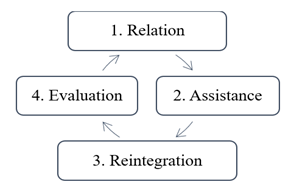

Sukabdi (2022) discovered changeable and unmodifiable characteristics of terrorist offenders in her study conducted in Indonesia. The results indicate that Motivation is subject to modification, whereas Ideology is more resistant to change, and Capability is typically immutable. Informed by these findings, a treatment protocol has been established and executed in Indonesia to rehabilitate generic terrorist offenders. Her research provides systematic interventions customized for offenders with diverse objectives, beliefs, attitudes, roles within ideological factions, levels of militancy, and competencies. The study by Sukabdi (2022) on the administration of treatment for terrorist offenders has been subsequently revised into the ‘RARE’ Model of Deradicalization (Relation-Assist-Reintegration-Evaluation) Figure 1, which comprises multiple processes as follows Sukabdi (2025):

1) Relation: a) Surveillance and Prevention, b) Attention, c) Hope, d) Rapport, e) Assessments, f) Objectives, g) Methods, h) Measurement, i) Preparation.

2) Assistance: a) Placement, b) Wellbeing, c) "Heart", d) "Head", e) "Hand".

3) Reintegration: a) New Identity, b) Empowerment, c) Reintegration, d) Advocacy.

4) Evaluation: a) Evaluation, and b) Upgrades.

4. Methods

This study employed a qualitative methodology to examine the application of AI in deradicalization efforts. The qualitative method was employed to acquire extensive information regarding AI-based deradicalization. Moreover, this study included a literature review to collect additional data. A literature review is a systematic approach of identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing previous research relevant to a specific topic. The literature review method serves as a basis and rationale for the study, ensuring it is informed by existing knowledge and academic discourse. Sukabdi (2025) 'RARE' Model of Deradicalization is wide-ranging; hence, it is employed in this study to provide a framework for the processes in deradicalization.

This study includes six AI professionals, two counterterrorism practitioners, and two prominent former offenders associated with Al Qaeda, Jamaah Islamiyah, and ISIS. All individuals were between the productive age bracket of 35 to 50 years. All of these practitioners operated in the security and military sector and were employed as consultants or full-time personnel within governmental agencies. The study participants were chosen based on their qualifications and/or endorsements from colleges and counterterrorism agencies. This study utilized purposive sampling to guarantee the inclusion of participants with substantial knowledge. To mitigate bias in purposive sampling, participants were selected based on a minimum of five years of experience, recommendations, and qualifications in the sector.

In terms of data collection, correspondence with participants were conducted followed by structured interviews with them. Interviews were performed in 2025 via telephone and in person in Seattle, United States, and Jakarta, Indonesia. The interview protocol is defined in Table 1. Every participant engaged in a solitary interview session lasting roughly ninety minutes. Interviews were conducted in English and Indonesian. For analysis, literature review combined with participants’ responses are used to describe the use of AI in deradicalization.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Interview Guideline |

|

Can artificial intelligence aid in

deradicalization efforts? |

|

In what ways may AI facilitate deradicalization

or alter the perspectives of extremists? Can you give an example? |

|

What

is your perspective on the plan for AI-driven deradicalization? |

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Opportunities of AI-Based Deradicalization

This study found that AI can be utilized in each step of deradicalization. The following are how AI can contribute to deradicalization:

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 The RARE Model of Deradicalization Sukabdi (2025) |

1) Relation

In the context of surveillance and detection for preventive measures, AI or machine learning algorithms can analyze substantial quantities of online data (social media posts, forums, blogs, chat rooms) to identify extremist content, recruitment messages, hate speech, or radicalizing storylines. Natural Language Processing (NLP) enables models to discern sentiment, tone, rhetorical structures, and repeated propaganda motifs. This facilitates the early identification of radicalizing trends or at-risk populations. AI can also analyze online behavior to identify individuals at risk of radicalization. While not deterministic, predictive models can highlight patterns of engagement with extremist content. In Indonesia, there is a view that AI can support Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) initiatives by facilitating social media surveillance and identifying abstract themes or feelings that suggest radicalization Mutiara (2025). Furthermore, AI can assist in personalizing and pattern recognition during the processes of introducing hope to terrorist offenders, establishing rapport, assessing, and preparing interventions. AI can assist in profiling risk patterns by assessing aggregated behavioral data, including online behavior, network connections, and content engagement, to detect probabilities or clusters. This facilitates the targeting of support services or counseling to persons at heightened risk Mutiara (2025).

2) Assistance

In the execution of intervention programs encompassing placement, wellbeing enhancement, emotional engagement, ideological discourse, and empowerment, the subsequent applications of AI may be utilized:

· Intervention via automated or semi-automatic tools.

Upon establishing detection, AI-driven systems can facilitate the implementation of interventions:

1) Chatbots or conversational agents capable of interacting with persons exhibiting radicalizing behavior, providing counter-narratives, information, referrals to support agencies, or even serving as a sympathetic listener (e.g. bots that engage or interact online to steer dialogue) Marcellino et al. (2020), Mutiara (2025).

2) Recommendation systems designed to deliver content (videos, readings, testimonials) that confront extremist beliefs and provide alternative, affirmative narratives Marcellino et al. (2020).

· Facilitating content control and platform regulation.

Social media platforms can utilize AI to identify, eliminate, or diminish the visibility of extremist content, hate speech, misinformation, and recruitment efforts. This restricts exposure. Research and proposals indicate that AI systems for content monitoring and collaboration with technology firms are under examination Al-Babli (2023), Marcellino et al. (2020).

3) Reintegration

· Tailored training, education, and livelihood matching. AI systems can create personalized learning trajectories (literacy, vocational training, digital skills) and connect returning individuals with local employment prospects or micro-economic initiatives—crucial components for sustained social reintegration and diminished recidivism. Pilot initiatives in correctional and reintegration settings demonstrate that AI can facilitate curriculum personalization and monitor success Cross et al. (2024), Youvan (2024).

· Decision support for local practitioners. Caseworkers, faith leaders, and NGOs/Non-Government Organizations staff at the community level often manage many beneficiaries with limited resources. AI-driven dashboards can synthesize risk indicators, flag individuals who need in-person follow up, and surface which interventions (mentorship, counseling, job placement) are producing the best outcomes (allowing scarce human resources to be prioritized more effectively). It is necessary to design prototype “support and monitoring” systems for community supervision that combine AI analytics with human case management.

· Community sentiment and early warning. Natural language processing (NLP) and social-listening tools can help local NGOs and municipalities detect rising polarizing or extremist narratives in community social media spaces (enabling pre-emptive, community-led dialogues or counter-narrative campaigns). However, practical utility depends on local language models and culturally aware tuning.

4) Evaluation

In evaluating and upgrading deradicalization programs, AI and statistical/mathematical modeling can facilitate the evaluation of program efficacy by quantifying disengagement, analyzing recidivism, and modeling the most effective components Sukabdi (2025). Moreover, mathematical modeling has been used to evaluate deradicalization programs, providing insights into their effectiveness and scalability Anandari (2022).

5.2. Challenges of AI-Based Deradicalization

Although promising, AI is not a panacea, as indicated by the participants of this study. The following are significant limitations and ethical risks to consider:

1) False positives or overreach: regrettably, misidentification of content or individuals can lead to unjustified censorship, privacy violations, suppression of legitimate speech, and alienation.

2) Bias: training data often reflects the biases of its source. AI systems may disproportionately flag content from certain groups or languages, or misunderstand cultural context.

3) Privacy concerns: monitoring people’s online behaviour raises issues of consent, data protection, surveillance, and human rights.

4) Effectiveness limits: deradicalization often depends heavily on human relationships, social context, psychological support, ideological debate, spiritual or religious mentorship (things AI cannot replicate in full). AI tools may catalyze or support these human interventions but rarely replace them. For example, deradicalization in Indonesia remains deeply rooted in personal relationships. Religious scholars such as KH. Hasyim Muzadi and organizations like Nahdlatul Ulama have been pivotal in promoting moderate interpretations of Islam. AI cannot replicate this trust and legitimacy but can support it by amplifying counter-narratives, identifying at-risk individuals, and streamlining program evaluation. As Horgan et al. (2020) argue, human engagement remains the foundation of deradicalization, with technology playing a supporting role.

5) Adversarial use: The same AI tools can be repurposed by malicious actors for targeted recruitment, disinformation, or synthetic content Davis (2021), Fernandez and Alani (2021), McKendrick (2019), Montasari (2024), Syllaidopoulos et al. (2025), Weimann et al. (2024). Extremist actors may adapt: changing language, moving to encrypted or private forums, using coded speech, deepfakes, synthetic media to evade detection.

6) Ethical trade-offs: between free speech and safety, privacy and monitoring, security interests and civil liberties. Misidentification could stigmatize innocent individuals. For example, biased data could disproportionately affect Muslim communities, reinforcing perceptions of Islamophobia Al-Babli (2023). Additionally, extremists increasingly shift to encrypted apps such as Signal and Telegram, reducing the reach of AI surveillance Abdullah et al. (2025), Raharjo et al. (2025). Hence, AI must be deployed alongside human oversight, transparency, and ethical guidelines to protect civil liberties Davis (2021), Fernandez and Alani (2021), McKendrick (2019), Montasari (2024), Syllaidopoulos et al. (2025).

5.3. Case Studies of AI-Based Derdicalization

Case Study 1: The Redirect Method

(Jigsaw/Moonshot/Google)

Overview. The Redirect Method is a practical demonstration of algorithmic targeting and ad-tech used as a deradicalization tool. Initially developed by Jigsaw (Google), Moonshot CVE, and partners, the method used keyword targeting in search and advertising platforms to serve alternative, counternarrative videos and resources to users searching for extremist material Helmus and Klein (2018). The idea: intercept intent signals (searches, video views) and present content that offers different narratives or pathways away from radicalizing material.

Implementation and metrics. The Redirect Method used search-term mapping and advertising placements (e.g., Google Ads/YouTube) to place counternarrative videos before or alongside extremist content. Process metrics reported include impressions, click-through rates, and watch time (metrics at or near industry norms) and stronger reach for some target audiences (e.g., jihadist search terms achieved very high impression share in some deployments) Helmus and Klein (2018). However, the evaluation largely remained a process evaluation: while the campaign successfully placed content in front of users, it did not demonstrate robust evidence of long-term attitude or behavior change among targeted individuals Helmus and Klein (2018), Windisch et al. (2022).

Lessons learned. Redirect shows that ad-tech can precisely reach audiences searching for extremist material and that standard digital metrics can measure exposure. It also highlights the evaluation challenge: process success (impressions, clicks) is simpler to measure than causally linking exposure to de-radicalization outcomes; rigorous experimental or longitudinal designs are needed to assess whether targeted counternarratives change beliefs or reduce violent intent Helmus and Klein (2018), Lewis and Marsden (2021), Windisch et al. (2022)

Case Study 2: WeCounterHate

(Life After Hate), AI for detection and intervention

Overview. Life After Hate, a U.S.-based intervention NGO, partnered with technical teams to build the WeCounterHate platform (also described as #WeCounterHate), an AI-driven system to identify toxic or hateful content on Twitter and prompt corrective action. The tool combined automated detection of abusive posts and automated outreach (e.g., prompting authors to delete or directing them toward help resources), and the initiative received recognition (Shorty Social Good Award) for applying ML to intervene in hateful behaviors online Land and Hamilton (2019), Life After Hate (2018), Shorty Awards (2018).

Implementation and effectiveness. WeCounterHate used ML classifiers to flag likely hate speech and automatic or semi-automated responses to steer behavior. The platform turned toxic retweets into an actionable intervention, e.g., nudging authors or highlighting donation links. Reports suggest promising proof-of-concept results in reducing the spread of targeted content and raising awareness, but like many deployments, peer-reviewed causal evidence on longer-term deradicalization impact (change in beliefs, recidivism into hateful communities) remains limited in published literature Land and Hamilton (2019), Life After Hate (2018).

Lessons learned. Automated detection plus human-in-the-loop moderation can scale interventions while preserving contextual judgment. However, classifier errors can produce harms: false positives may chill legitimate speech, and poorly calibrated outreach can backfire with target audiences McKendrick (2019), Windisch et al. (2022).

Case Study 3: Platform and industry collaborations

(gaming and platform safety)

Overview. Industry coalitions such as the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) and platform-specific safety efforts increasingly employ AI for content detection, removal, and prevention across social media and gaming environments. Recent work has extended to specialized domains (e.g., gaming) where community dynamics and in-game harassment can provide vectors for radicalization Schlegel (2024).

Implementation and evidence. Platform firms use ML models to detect extremist text, images, and network behaviors and to prevent reuploading via hash-matching and similarity detection. Industry documents and reports show growing sophistication (multimodal detection, embeddings, network analysis), but also persistent challenges in domain adaptation, adversarial evasion, and the need for human review to handle contextual nuance Davis (2021), Fernandez and Alani (2021), Montasari (2024), Schlegel (2024), Syllaidopoulos et al. (2025).

Lessons learned. Platform-level AI is central to content moderation and deradicalization pipelines, yet platform incentives, transparency, and cross-platform coordination remain critical governance issues. Industry coalitions can share threat signals and best practices, but independent evaluation and privacy safeguards are necessary to ensure legitimacy Lewis and Marsden (2021), Schlegel (2024).

Case Study 4: Local and national programs by

Indonesia’s BNPT

Overview. Indonesia has long invested in deradicalization and reintegration programs for detainees and communities. Recent local studies and program descriptions highlight how social media literacy campaigns and targeted online engagement (sometimes integrating digital tools) have been combined with offline psychosocial support and community reintegration Anindya (2019), Mohammed (2020), Ilyas and Athwal (2021), Suarda (2016), Sipayung et al. (2023). Moreover, Figure 2 demonstrates the comparison of Indonesia’s deradicalization programs and potential AI contributions Abror and Wahrudin (2025), Anindya (2019), Davis (2021), Fernandez and Alani (2021), Gunton (2022), Hussain et al. (2018), Ilyas and Athwal (2021), Ismed and Ismed (2021), Lim (2017), Mohammed (2020), Montasari (2024), Syllaidopoulos et al. (2025), Suarda (2016), Sipayung et al. (2023), Sukabdi (2018), Sukabdi (2022), Windisch et al. (2022).

1) BNPT

Prison Deradicalization Program

Indonesia’s prison-based deradicalization program focuses on rehabilitating convicted terrorists through dialogue with psychologists, religious scholars, and former militants. While these efforts have had mixed success, AI could improve monitoring of inmates’ communication to detect ongoing extremist influence. For example, AI text analysis tools could identify coded messages in prisoner correspondence, reducing the risk of continued radical networking within prisons International Crisis Group (2017).

2) Community-Based

Deradicalization

BNPT also partners with local religious leaders and NGOs to run community resilience programs, such as Forum Koordinasi Pencegahan Terorisme (FKPT). AI could enhance these initiatives by analyzing social media conversations within local communities to identify rising extremist sentiments, thereby enabling targeted educational campaigns. This is particularly relevant in rural and semi-urban areas where radical groups recruit through religious study circles (pengajian).

3) Online

Counter-Narratives

Indonesia has experimented with online counter-narratives, such as the Voice of the Peaceful Generation campaign led by youth influencers. AI-based recommender systems could optimize the distribution of these videos and articles to audiences most vulnerable to radicalization. By using algorithms similar to those employed by commercial advertising, AI could maximize exposure of peace-oriented content to susceptible groups.

Implementation and evidence. Indonesian programs emphasize a hybrid model: in-prison education, family and community reintegration, and online counter-messaging tailored to local languages and cultural contexts. Academic reviews find that media literacy and community engagement improve public resilience to extremist messaging; however, systematic measurements of AI components specifically remain scarce in public scholarship Suarda (2016), Sipayung et al. (2023).

Lessons learned. Context matters: locally tailored messages, credible messengers (including former extremists), and combining offline services with online interventions strengthen plausibility and community acceptance. AI can support scaling these efforts (targeting, monitoring) but cannot replace human judgment and culturally grounded rehabilitation services Suarda (2016), Sipayung et al. (2023).

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Comparison of Indonesia’s Deradicalization Programs and Potential AI Contributions |

5.4. Evidence, assessment, and methodological obstacles

A recurring element in case studies is the challenge of evaluation. Numerous AI treatments document process metrics (impressions, flags, clicks), although fewer furnish substantial evidence that exposure induces alterations in beliefs, intentions, or recidivism. RAND's examination of the Redirect Method advocates for experimental designs, longitudinal studies, and mixed-methods strategies, which involve enlisting former extremists to evaluate content relevance Helmus and Klein (2018). Systematic evaluations highlight the variability of effects and the necessity for standardized criteria that link online interaction to offline behavioral change Lewis and Marsden (2021), Windisch et al. (2022).

5.5. Practical Implementation Considerations

For AI-based deradicalization to work effectively in practice, several interconnected elements must be addressed. Participants in this study emphasized that these are not optional add-ons but foundational requirements for building trustworthy and socially responsible systems.

First, success in this field depends heavily on multidisciplinary collaboration. AI and data science may provide the technical infrastructure, but radicalization is deeply rooted in human behavior, belief systems, and social environments. Insights from psychology, sociology, theology, and law are therefore critical. Likewise, the involvement of local community actors, educators, and religious leaders ensures that interventions are both contextually relevant and ethically defensible.

Second, localization is essential. Extremist ideologies often exploit specific grievances, cultural narratives, and religious symbols. A universal model risks misinterpretation and alienation, while locally adapted tools (i.e., sensitive to language, idioms, and cultural practices) resonate more authentically with communities.

Third, transparency and oversight are needed to safeguard legitimacy. Clear rules about what is monitored, how data is processed, and who is responsible must be established. Oversight by independent or community bodies helps prevent abuse and fosters public trust. Closely tied to this is privacy and data protection. Minimal data collection, anonymization, explicit consent, and secure storage are crucial safeguards to protect individuals’ rights while reinforcing program credibility.

Another central principle is human-in-the-loop design. While AI can rapidly process large volumes of data, it should function as an assistive tool rather than the sole decision-maker. Human reviewers provide the contextual sensitivity and moral judgment necessary for interpreting nuanced speech, particularly in religious or political contexts Windisch et al. (2022). Finally, rigorous evaluation is indispensable. Programs must include mechanisms for measuring real-world impact rather than relying only on process metrics. Longitudinal studies, experimental designs, and feedback loops can determine what works, what fails, and why, allowing programs to be refined and adapted over time. Taken together, these elements highlight that AI-based deradicalization is not purely a technical challenge but a social endeavor. Its success depends on careful design, ethical responsibility, and collaboration across diverse fields.

5.6. Future Directions of AI-based Deradicalization

Anticipating future developments, AI-driven deradicalization is expected to progress in reaction to technical advancements and the threats presented by extremist entities. Participants in this survey recognized other domains in which the field could progress.

A significant trend is the advancement of more complex natural language processing (NLP) models. Extremist rhetoric frequently utilizes coded terminology, analogies, and allusions that circumvent standard recognition. Training AI systems to identify these nuances will facilitate the differentiation between authentic conversation and initial indicators of radicalization, thereby allowing for prompt and suitable actions.

A further interesting approach is the development of real-time intervention tools. AI-powered chatbots or virtual counselors could interact with at-risk persons in a supportive and non-confrontational manner. These technologies might engage empathetically, present viable choices, and, when required, escalate high-risk instances to human counselors. These hybrid solutions would integrate the scalability of artificial intelligence with the discernment of human judgment.

The increasing prevalence of synthetic media and deception poses an additional issue. Extremist organizations are increasingly utilizing deepfakes and altered films to disseminate misinformation. AI-driven detection technologies that can identify counterfeit content and indicate its inauthenticity will be essential for preserving information integrity and public trust. Moreover, predictive risk modeling might facilitate preventive outreach if implemented judiciously. Meticulously crafted models may assist in recognizing trends indicative of a path toward radicalization. Nonetheless, these instruments pose significant ethical hazards, such as stigmatization and erroneous positives, and must consequently function within transparent, rights-oriented frameworks.

The incorporation of AI into comprehensive/broader deradicalization and reintegration initiatives presents substantial promise. AI tools could be integrated into jail education programs, community reintegration services, or school-based projects instead of functioning as independent systems. They could, for example, assist in personalizing educational materials or monitoring progress in rehabilitation. When combined with mentorship, psychosocial support, and community participation, AI can serve as a force multiplier, connecting online interventions with offline realities.

The future of AI-driven deradicalization hinges on the equilibrium between innovation and accountability. Progress in natural language processing, real-time interaction, fraud detection, predictive analytics, and program integration presents significant prospects. Their efficacy will rely on meticulous governance, ethical protections, and ongoing cooperation among technologists, legislators, and local populations.

6. Conclusion

The exploration of AI-based deradicalization highlights both its promise and its limitations. On one hand, AI offers powerful tools for analyzing extremist discourse, monitoring risk, and expanding the reach of prevention programs. On the other hand, its effectiveness relies not on technology alone but on integration with social, cultural, and psychological dimensions of radicalization. Deradicalization is fundamentally a human-centered process, and AI can only serve as an assistive mechanism to strengthen, not replace, the role of trust, empathy, and dialogue in countering extremism.

A major finding of this study is that implementation requires careful attention to practical considerations. Multidisciplinary collaboration is indispensable, as technological expertise must be combined with psychology, sociology, theology, human rights, and community engagement. Radicalization cannot be understood or addressed solely as a technical problem; it is a phenomenon embedded in local grievances, cultural narratives, and identity struggles. AI, when deployed without contextual sensitivity, risks oversimplifying complex social realities and undermining the legitimacy of interventions.

Equally significant is the need for localization. AI systems must be adapted to community languages, idioms, and norms, as generic or one-size-fits-all models often misinterpret nuanced communication. Participants of this study emphasized that tailoring AI tools to cultural contexts not only improves accuracy but also builds credibility with target communities. Localization thus becomes an ethical as well as a technical necessity, ensuring that interventions are authentic and not perceived as external impositions.

Ethical safeguards emerged as another crucial pillar. Transparency, oversight, and data protection are essential to prevent misuse of sensitive personal information. Without clear accountability frameworks, AI-driven monitoring risks eroding public trust and infringing on civil liberties. Human-in-the-loop design is a practical way forward, ensuring that AI-generated insights are always complemented by human judgment in sensitive decision-making processes. Such hybrid systems preserve fairness, proportionality, and contextual understanding.

Looking to the future, technological advances present both opportunities and risks. Developments in natural language processing promise more nuanced recognition of extremist symbols and coded discourse, while real-time intervention tools such as AI-driven chatbots could provide supportive alternatives for individuals engaging with extremist content online. At the same time, the growing sophistication of synthetic media underscores the urgent need for AI tools capable of detecting and countering deepfakes and manipulated propaganda. These innovations, however, must be embedded within broader governance frameworks to prevent overreach or misuse.

The study also underscores the importance of evaluation and iterative learning. Too often, deradicalization initiatives are launched without robust mechanisms for measuring outcomes. AI has the potential to fill this gap by providing data-driven insights into program effectiveness, but this requires rigorous methodologies, longitudinal analysis, and openness to refinement. Only through continuous evaluation can deradicalization programs evolve to meet changing extremist strategies and social dynamics.

Ultimately, the conclusion of this study is that AI’s role in deradicalization is one of augmentation rather than substitution. Technology can strengthen surveillance, enhance intervention, and scale educational outreach, but the heart of deradicalization remains human: relationships, trust, mentorship, and dialogue. If designed with sensitivity, accountability, and collaboration, AI can become a valuable ally in building resilience against extremism. Yet its success will depend less on its technical sophistication than on whether it is deployed in ways that respect human dignity, safeguard rights, and empower communities.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None .

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Abdullah, M., Amiruddin, M. H., Dewi, E., and Mannan, N. H. (2025). Moderation of Thought in the Age of Radicalism: The Role of Social Media and Political Education in Countering Hate Content. Tafkir: Interdisciplinary Journal of Islamic Education, 6(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.31538/tijie.v6i1.1373

Abror, S., and Wahrudin, B. (2025). Countering Religious Extremism: Innovative Deradicalization Strategies for Building Inclusive Communities. MUNIF: International Journal of Religion Moderation, 1(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.71305/munif.v1i1.448

Al-Babli, A. (2023). Artificial Intelligence Mechanisms in Countering Violent Extremism. Journal of Police and Legal Sciences, 14(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.69672/3007-3529.1015

Anandari, A. A. (2022). Mathematical

Modeling to Measure the Level

of Terrorism Deradicalization

Effectiveness. IJID (International Journal on Informatics for Development),

11(1), 202–211.

Anindya, C. R. (2019). The Deradicalisation Programme for Indonesian Deportees: A Vacuum in Coordination. Journal for Deradicalization, (18), 217–243.

Aslam, M. M. (2019). De-Constructing Violent Extremism: Lessons from Selected Muslim Countries. DINIKA: Academic Journal of Islamic Studies, 4(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.22515/dinika.v4i1.1708

Aslam, M. M. (2020). Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism: Lessons from Selected Muslim Countries. Islam Realitas: Journal of Islamic and Social Studies, 6(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.30983/islam_realitas.v6i1.3152

Cross, S., Bell, I., Nicholas, J., Valentine, L., Mangelsdorf, S., Baker, S., Titov, N., and Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2024). Use of AI in Mental Health Care: Community and Mental Health Professionals Survey. JMIR Mental Health, 11, e60589. https://doi.org/10.2196/60589

Davis, A. L. (2021). Artificial Intelligence and the Fight Against International Terrorism. American Intelligence Journal, 38(2), 63–73.

Dobrev, D. (2013). Comparison Between the Two Definitions of AI. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1302.0216

Fernandez, M., and Alani, H. (2021). Artificial Intelligence and Online Extremism: Challenges and Opportunities. In Predictive policing and artificial intelligence (132–162). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429265365-7

Gunton, K. (2022). The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Content Moderation in Countering Violent Extremism on Social Media Platforms. In Artificial intelligence and national security (69–79). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06709-9_4

Helmus, T. C., and Klein, K. (2018). Assessing Outcomes of Online Campaigns Countering Violent Extremism: A Case Study of the Redirect Method (RAND RR-2813). RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2813

Horgan, J., Meredith, K., and Papatheodorou, K. (2020). Does Deradicalization Work? In A. Silke (Ed.), Radicalization and Counter-Radicalization (239–260). Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1521-613620200000025001

Hussain, M. N., Tokdemir, S., Agarwal, N., and Al-Khateeb, S. (2018). Analyzing Disinformation and Crowd Manipulation Tactics on YouTube. In 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM) (1092–1095). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASONAM.2018.8508766

Ilyas, M., and Athwal, R. (2021). De-Radicalisation and Humanitarianism in Indonesia. Social Sciences, 10(3), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10030087

International Crisis Group. (2017). How Indonesian Extremists Regroup (Asia Report No. 287).

Irfan, M., Almeshal, Z. A., and Anwar, M. (2023). Unleashing Transformative Potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Countering Terrorism, Online Radicalisation, Extremism and Possible Recruitment. Global Strategic and Security Studies Review, 8(IV), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.31703/gsssr.2023%28VIII-IV%29.01

Ismed, D. M., and Ismed, S. H. (2021). Deradikalisasi Penanganan Terorisme Secara terintegrasi di Indonesia. Jurnal Penelitian Hukum Legalitas, 15(2), 59–64.

Karam, M., and Luck, M. (2023). Approaching AI: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Using AI for HCI. In Interacción. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35891-3_32

Koehler, D. (2016). Understanding Deradicalization: Methods, Tools and Programs for Countering Violent Extremism. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315649566

Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., Bélanger, J. J., Sheveland, A., Hetiarachchi, M., and Gunaratna, R. K. (2014). The Psychology of Radicalization and Deradicalization: How Significance Quest Impacts Violent Extremism. Political Psychology, 35, 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12163

Land, M. K., and Hamilton, R. J. (2019). Beyond Takedown: Expanding the Tool Kit for Responding to Online Hate. In Propaganda and international criminal law (143–156). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429443695-7

Leap, B., and Young, J. (2021). Radicalization and Deradicalization. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.601

Lewis, J., and Marsden, S. (2021). Countering Violent Extremism Interventions: Contemporary Research. Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats.

Life After Hate. (2018). Intervention Archives – #WeCounterHate.

Lim, M. (2017). Freedom to Hate: Social Media, Algorithmic Enclaves, and the Rise of Tribal Nationalism in Indonesia. Critical Asian Studies, 49(3), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2017.1341188

Maas, M. M. (2023). Concepts in Advanced AI Governance: A Literature Review of Key Terms and Definitions. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4612473

Marcellino, W., Magnuson, M., Stickells, A., Boudreaux, B., Helmus, T. C., Geist, E., and Winkelman, Z. (2020). Counter-Radicalization Bot Research: Using Social Bots to Fight Violent Extremism (RR-2705). RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR2705

McKendrick, K. (2019). Artificial Intelligence: Prediction and Counterterrorism. Chatham House.

Mohammed, I. (2020). Critical Reflections on De-Radicalisation in Indonesia. Otoritas: Jurnal Ilmu Pemerintahan, 10(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.26618/ojip.v10i1.3097

Montasari, R. (2024). Addressing Ethical, Legal, Technical, and Operational Challenges in Counterterrorism with Machine Learning: Recommendations and Strategies. In Cyberspace, Cyberterrorism and the International Security in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Threats, Assessment and Responses (199–226). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-50454-9_10

Mutiara, R. (2025, July 17). The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Countering Online Radicalisation in Indonesia (RSIS Commentary No. CO25157). S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

Nedilko, B. (2024). Concept and Main Characteristics of Artificial Intelligence: Domestic and Foreign Approaches. Modern Scientific Journal. https://doi.org/10.36994/2786-9008-2024-5-2

Noor, A. M., and Fauziyah, N. (2022). Humanistic Deradicalization by Abraham Maslow Approach: Terrorism Counter-Measures Strategy in Lingkar Perdamaian Foundation. Tajdid: Jurnal Ilmu Ushuluddin, 21(1), 125–149. https://doi.org/10.21043/addin.v15i2.14352

Porta, D. D. (2018). Radicalization: A Relational Perspective. Annual Review of Political Science, 21, 461–474. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042716-102314

Raharjo, A., Retnaningrum, D. H., Sugeng, E., Saefudin, Y., and Ismail, N. (2025). Radicalization and Counter-Radicalization on the Internet (Roles and Responsibilities of Stakeholders in Countering Cyber Terrorism). In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 609, Article 07003). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202560907003

Schlegel, L. (2024). Preventing and Countering Extremism in Gaming Spaces. In Preventing and Countering Extremism in Gaming Spaces (Chapter 11). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003388371-11

Sholehuddin, S., Ahmad, G., and Zam, R. Z. (2024). Terrorism Deradicalization Management Based on Education on the Principles of Islamic Teaching. International Journal of Educational Narratives, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.70177/ijen.v2i4.1141

Shorty Awards. (2018). WeCounterHate – Shorty Social Good Award Entry.

Sipayung, A., Soleh, C., Rochmah, S., and Rozikin, M. (2023). Dynamics Implementation of De-Radicalism Policy to Prevent Terrorism in Indonesia: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 11(9), e772. https://doi.org/10.55908/sdgs.v11i9.772

Suarda, I. G. W. (2016). A Literature Review on Indonesia’s Deradicalization Program for Terrorist Prisoners. Mimbar Hukum, 28(3), 526–543. https://doi.org/10.22146/jmh.16682

Sukabdi, Z. A. (2018). Psychological Rehabilitation for Ideology-Based Terrorism Offenders. In Deradicalisation and terrorist rehabilitation (95–116). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429469534-7

Sukabdi, Z. A. (2022). Treatment Procedures for Ideology-Based Terrorist Offenders in Indonesia. Kriminologija and Socijalna Integracija, 30(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.31299/ksi.30.1.1

Sukabdi, Z. A. (2025). Psikologi Terorisme [Psychology of terrorism]. Bumi Aksara.

Sumarwoto, S., Hr, M., and Khisni, A. (2020). The Concept of Deradicalization in an Effort to Prevent Terrorism in Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.25134/unifikasi.v7i1.2703

Syllaidopoulos, I., Ntalianis, K., and Salmon, I. (2025). A Comprehensive Survey on AI in Counter-Terrorism and Cybersecurity: Challenges and Ethical Dimensions. IEEE Access, 13, 91740–91764. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3572348

Wahyuni, S., Syaripudin, M., Aglina, E. F., Zamhariri, Makmun, F., Achlami, Hidayat, M., and Fitri, E. (2025). Artificial Intelligence for Moderate Da’wah Communication: Science Perspective. KnE Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v10i14.19076

Weimann, G., Pack, A. T., Sulciner, R., Scheinin, J., Rapaport, G., and Diaz, D. (2024). Generating Terror: The Risks of Generative AI Exploitation. CTC Sentinel, 17(1), 17–24.

Windisch, S., Wiedlitzka, S., Olaghere, A., and Jenaway, E. (2022). Online Interventions for Reducing Hate Speech and Cyberhate: A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 18(2), e1243. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1243

Youvan, D. (2024). Artificial Intelligence in Correctional Facilities: Enhancing Rehabilitation and Supporting Reintegration. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.27649.67681

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© DigiSecForensics 2025. All Rights Reserved.